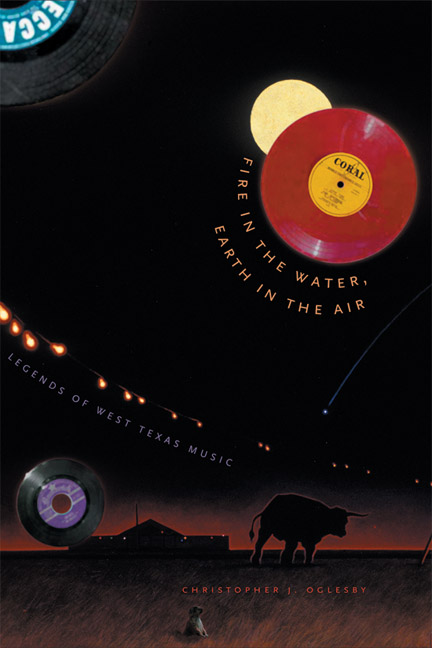

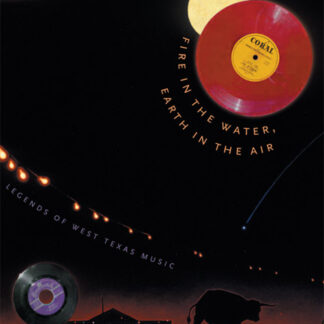

Description

Buy this popular book directly from us and author Christopher J. Oglesby will sign & personalize your copy.

In this award winning book, Christopher Oglesby interviews twenty-five musicians and artists with ties to Lubbock to discover what it is about this community and West Texas in general that feeds the creative spirit. This kaleidoscopic portrait of the West Texas music scene gets to the heart of what it takes to create art in an isolated, often inhospitable environment. As Oglesby says, “Necessity is the mother of creation. Lubbock needed beauty, poetry, humor, and it needed to get up and shake its communal ass a bit or go mad from loneliness and boredom; so Lubbock created the amazing likes of Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Butch Hancock, Terry Allen, and Joe Ely.”

From the Book’s Introduction

Since Lubbock is the place where the earth is in the air and the fire is in the water, it’s naturally got to be the place where the music gets tied up in knots and comes out unraveled.

—Jimmie Dale Gilmore

I grew up like most other folks in Lubbock. I went to church, where my mom taught Sunday school every Sunday, until I moved out of my parents’ house to attend Texas Tech University. Like many other Tech students in the 1980s, I found my weekend rituals at Fat Dawg’s, the Main Street Saloon, the Texas Spoon Café, and P. J. Belly’s. I discovered, as everyone who has lived there knows, that all the social and cultural action in Lubbock happens either in churches or bars. After eighteen years of going to church every Sunday morning with my mother, Saturday night at Fat Dawg’s saloon became both school and church to me. The sober Presbyterians on 33rd Street did not offer the spiritual revival of a Joe Ely show, with Jesse Taylor on electric guitar, Lloyd Maines on pedal steel, and often Rolling Stones saxophone player Bobby Keys blowing the crowd to high heaven with exultant solos.

When I learned as a teenager that Buddy Holly had attended Roscoe Wilson Elementary, Hutchinson Junior High, and Lubbock High, the same public schools I attended, I became enchanted knowing an artist of worldwide importance could come from my seemingly normal neighborhood. After receiving two degrees from Texas Tech University, I moved to Austin, where I became more aware that Lubbock’s fame for producing songwriters, musicians, and artists is equal to its renown for cotton, conservatives, and windstorms. I have interviewed many of these artists over the years, searching for an answer to that oft-asked question: “Why Lubbock?” This book is the product of that exploration.

Fire in the Water

In 1989 the first President George Bush responded to accusations that the U.S. economy was adrift in malaise, “All the people in Lubbock think things are going great.” Since then, Lubbock has been considered a leading standard-bearer for American conservatism. Much of the Lubbock community is proud of that fact. Nowhere does the GOP enjoy such universal popularity as it does in Lubbock. In the 2004 election, 75 percent of those voting a straight ticket in Lubbock County voted Republican. Among the seven largest metropolitan areas in Texas, Lubbock County had the highest percentage voting for George W. Bush in 2004, also 75 percent. Ranked in 2005 as the second-most-conservative U.S. city, Lubbock proudly occupies the vanguard of the Republican Revolution of the early twenty-first century. This is despite the irony that would-be assassin John Hinckley was living in Lubbock in 1981 when he bought the gun he later used to shoot President Reagan.

Perhaps equally as ironic, on March 10, 2003, Lubbock native Natalie Maines was one of the first to publicly question the war agenda of fellow West Texan President George W. Bush. Natalie made her now famous statement, “Just so you know, we’re ashamed the president of the United States is from Texas,” between songs in Shepherd’s Bush Empire, an intimate London concert hall that seats fewer than 1,500 people. She did not intend to issue a formal statement to the press or anticipate the reaction. In case you missed it, she caught a lot of flak for it back in the USA, and not the least of the criticism came from Lubbock. A sample of the hundreds of open letters addressed to Natalie Maines and posted to the Web site of the leading country music station in Lubbock said: “For you to travel to a foreign land and publicly criticize our Commander in Chief is cowardice behavior. Would you have so willingly made those comments while performing for a patriotic, flag-waving crowd of Texans in Lubbock? I would imagine not. I am returning to you each and every Dixie Chicks CD and cassette that I have ever purchased.” Furthering the irony, Natalie’s uncle Kenny Maines happened to be a popular Republican Lubbock County commissioner at the time.

It is not an over-generalization to say that, to many in Lubbock, the terms liberal and progressive are insults often spoken with disdain equal to that associated with such loaded words as faggot or nigger. In a 2005 PBS documentary film about the effects of Lubbock’s “abstinence only” sex education policy, the Lubbock pastor who directs the city’s True Love Waits sex education program expresses a prevalent local attitude when he states, “The terms Christian and liberal are like oil and water. It is true that Christianity is the most intolerant of religions, and I’m proud of that.”

It is frequently said that Lubbock has a church on every street corner. Of course, that is exaggeration. However, Lubbock does have many more than its share of churches. There are almost eight times as many churches per capita in Lubbock than in the United States as a whole. Broadway Street in downtown Lubbock is dominated by six major churches on a one-mile strip, each church an entire block long. The three largest churches on this devout avenue, Broadway Church of Christ, First United Methodist, and First Baptist, are among the largest congregations in the world of their respective denominations. Of the other churches in Lubbock, forty-eight are Baptist, thirty are Church of Christ, and twenty-six are Methodist.

West Texas is a land of paradoxes. Despite such avid church attendance, Lubbock has double the national average of sexually transmitted diseases in teenagers and has among the highest teenage pregnancy rates in the country. These facts support the theory: Tell a kid enough times not to do something and the kid will figure out that it must be fun for some reason. That alone may be enough to explain the wealth of rock ‘n’ roll, country, blues, and jazz artists who come from Lubbock.

Many people from West Texas believe its most valuable natural resource to be the character of the people who reside there. Even the most rebellious rock ‘n’ roll prodigals from Lubbock concede that West Texas people are exceptional in their commitment to values such a hard work, honesty, charity, and friendliness. Mac Davis, who coined the phrase “Happiness is Lubbock, Texas, in my rearview mirror,” when asked about his hometown, replies, “Let me put it this way: If I was going to have a flat tire without a spare, Lubbock is where I’d like to be.”

However, in conservative Lubbock, one frequently is deemed to fall into one of two groups; one is either a “partier” or a “churchgoer.” The churchgoers govern the town, while the partiers serve as the vocal counterculture. This duality is frequently the cause of much friction for the Lubbock music community. Musicians who must ply their trade in nightclubs and bars are almost always considered partiers and therefore on the underside of the community. But such subterranean friction creates powerful, potentially earthshaking energy. Place into this environment an artistic individual who sees reality a little differently than the rest, someone with creative genius, and we have an awesome potential for a new synthesis, and we’re all a little bit closer to the truth for it.

When I began my quest to chronicle the legends of Lubbock music, I spoke with guitar player Jesse Taylor, the first white man to ever play at the original Stubb’s Barbecue in East Lubbock. I told Jesse about being young and going with my dad to the now legendary Stubb’s. My dad was the basketball recruiter at Texas Tech during the late 1960s and ’70s, and he brought the first black collegiate basketball players to Lubbock in 1969, not without controversy. Also, books on the subject of barbecue have cited my dad as one of the foremost authorities on Texas barbecue joints. Although he is not much of a loud music fan, my dad had no qualms about taking me over to Lubbock’s east side (which means the black side of town) in search

of the best barbecue in West Texas. However, very few other white people ever made the journey to the east side to visit Stubb’s, at least not until Jesse Taylor and Stevie Ray Vaughan started rocking the joint at Stubb’s Sunday Night Jams. Being over there in the dark side of one of the most white-bread towns in America, I remember thinking, even as a youth, “There is something cool here. Why doesn’t anyone in Lubbock know about it or acknowledge it?” C. B. Stubblefield (“Stubb”) closed the small barbecue restaurant in 1984 due to poor finances, and moved to Austin, where several of his friends such as Joe Ely were living. Shortly before he died in 1997, Stubb reopened Stubb’s Barbecue in downtown Austin, where it is now one of the premier live music venues in the Live Music Capital of the World.

I told all this to Jesse Taylor during our first phone conversation and he agreed. “Sometimes I think that Lubbock will never change,” Jesse responded. “They don’t know what genius they have from right there in Lubbock. They could have built recording studios and turned Lubbock into the Nashville of Texas music but they just turn their backs.” He added: “But Austin is almost the same. It’s not at all like Lubbock in that Austin is very open-minded and liberal, but even in Austin, the people here don’t have any idea how much all us guys from Lubbock have done. I’ll go on tour with Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen and when I get back to Austin people come up to me and say, ‘Hey, Jesse, why haven’t you been playing down at the Saxon Pub lately?’ People just don’t know what they have here.”

A verse from the Bible has resounded in my mind as I have studied the paradox that is West Texas music and art. “No prophet goes without honor, except in his own country and among his own kin, and in his own home” (Mark 6:4). Perhaps any examination of conservative West Texas must begin by considering the Bible.

The King James Version of the Bible is the seminal text of the English language. Until the late nineteenth century, the KJV was commonly the only book most English speakers owned or read. It has been said that every metaphor, symbol, and story theme in the English language is based on the sacred stories in the King James Bible, and with good reason: These are very good stories. Virtually all truths are contained in this contradictory, poetic, magical epic of humanity’s violent struggle to enter the Kingdom of God.

The fact that the Lubbock community remains deeply immersed in the language and themes of the Bible in a way that may have become unpopular as America has entered the twenty-first century may be one explanation why Lubbock is noted for producing such exceptionally talented storytellers, poets, and lyricists.

Earth in the Air

Moreover, we must consider the uniqueness of the land of West Texas. People in Lubbock thrive in a territory of boundless horizons. In the vast emptiness of the South Plains, there is limitless room for the dreams of creative spirits.

However, to most folks, the land around Lubbock appears to be a broad, flat expanse of nothingness. There are no natural trees, no hills, no streams. For the predominantly Anglo-Saxon Protestant farmers who chose to settle in this unlikely semiarid landscape at the end of the nineteenth century, all Lubbock had to offer was the soil, and plenty of it. As historian Richard Mason explains, the cotton industry has been predominant on the High Plains of West Texas since emigrants, mostly from the Deep South states, fled the ravages of the boll weevil and sought inexpensive lands and a chance for a future out West.

The land was inexpensive because no white man had figured out how anyone could live out there on the vacant plains. However, these thick-skinned, no-nonsense immigrants settled on this inhospitable prairie to work the land for all the wealth to be reaped from it, not to enjoy the scenery. No one in his or her right mind settled in West Texas without being focused on the soil alone. Most westward-moving, prosperity-seeking Americans were bypassing the empty outback and forging on to the lush West Coast to California, Oregon, and Washington. Only the truly imaginative saw prosperity on the empty, arid central grasslands.

Naturalist and Texas Tech professor Dan Flores has noted Americans’ historical attitudes toward the Plains:

For a species whose evolution was shaped so much by a plains setting, we humans—especially we Americans—have never found much to admire in plains country other than skies. This is another aspect of our cultural preparation; since the time of Thomas Jefferson, scenery for Americans has meant mountains. . . . This discourages plains people. They look around them at the smooth line of the horizon, see no mountains in any direction, and accept the widespread consensus that the region is unlovely and, perhaps, not much worthy of love.

Many of the people who settled in West Texas brought with them the true American spirit of rugged individualism. Being isolated from the rest of the nation by endless miles of empty prairie, many West Texans discovered that if any joy was to be found in life it was to come from deep inside the heart, mind, and soul. When exposed on the West Texas plains, you are the tallest vertical object around, all that is between the land below and the sky above. It’s easy, standing there in that vast sea of prairie, to see the face of God staring back.

“Nothing else to do” is the frequent answer to the question “Why do so many innovative musicians come from Lubbock?” This void, the absence of external natural stimulation, as for the biblical holy men in the Sinai desert, can cause an individual to journey into the hidden spaces inside the human heart and mind, perhaps to discover marvelous mysteries deep within the spirit of mankind. With no surrounding external beauty, a sensitive individual tends to search for beauty and truth deep inside the heart and mind. Stimulation must come from within because there damn sure is nothing outside there on the plains to stimulate the mind, nothing other than the drive for survival in that vast island of prairie.

Necessity is the mother of creation. Lubbock needed beauty, poetry, humor, and it needed to get up and shake its communal ass a bit, or go mad from loneliness and boredom; so Lubbock created the amazing likes of Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Butch Hancock, Terry Allen, and Joe Ely.

But first there was Buddy Holly. Buddy, the putative father of American rock ‘n’ roll, was certainly a prophet of his age, an age awash in broadcasted recorded music. All our twenty-first-century minds, regardless of geography and language, are filled with the sounds of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Elton John, the Clash, the Ramones, etc., and all of these influential artists were directly and indelibly inspired by Buddy Holly.

If one takes the time to go to Lubbock, Texas, and speak with people who lived there at the time Buddy Holly was growing up, one will discover that many of Buddy Holly’s former peers and neighbors think very little of the man who became a worldwide icon of the rock ‘n’ roll era. They do not think poorly of him; most everyone who knew Buddy agrees that he was a good-hearted boy. Rather, most people who grew up in Lubbock with Buddy Holly think very little about him at all. It doesn’t take long in Lubbock to realize that most really did consider Buddy Holly an oddball. Of course, prodigies often do seem odd and out of place in mundane surroundings.

According to his contemporary Lubbockites, Buddy always had that strange misfit demeanor that seems so poignantly illustrated by those startling horn-rimmed glasses that were his trademark. Most people in Lubbock, other than a few teenagers like Sonny Curtis, Bobby Keys, and Waylon Jennings, paid little attention to young Buddy Holly. After all, he was just a boy the entire time he lived there. He had been out of Lubbock High School for only three years before his fateful death in the winter of 1959. Buddy was already recording by the age of fourteen. People in Lubbock simply remember him, if at all, as “that crazy boy who always carried around a guitar,” a miscreant kid piddling away his time with electronic noise.

In the religious, agricultural town of Lubbock, one is respected if he works hard and has something to show for it. Music is appreciated, but only as something you do in your free time, not as an occupation. For many years after Buddy’s death, the Lubbock community paid little regard to the earthshaking influence their most famous child had on the world.

Buddy went directly from local teenage misfit to international rock ‘n’ roll messiah in four short years. Buddy’s creative vision would change the world for us all. While Elvis will always be the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Buddy Holly is most certainly its George Washington. Buddy Holly gave hope to all the outcasts, misfits, artists, dreamers, shakers, wailers, and moaners of the world that if goofy old Buddy Holly could make it, they could, too. As Paul McCartney of middle-class Liverpool observed, “Buddy Holly gave you confidence. He was like the boy next door.” Buddy Holly and the Crickets were literally the first garage band, a self-contained four-piece ensemble: two guitars, bass, and drums, and a charismatic singer out front, writing and recording their own songs. This would prove to be the standard for all rock ‘n’ roll bands to come.

However, it is easy to make heroes out of the dead, because the dead can be whatever we want them to be. One aim of this book is to honor Lubbock’s living artists, to recognize their various contributions to art, music, and culture in Texas and the world.

Several generations of artists and writers have emerged somehow from Lubbock to influence popular music and art in significant and subtle ways. So the question is posed: Why does an isolated, conservative agricultural town like Lubbock, Texas, generate such innovative artists in numbers that seem so disproportionate to its population?

Is it the UFOs, the famed “Lubbock Lights” that hovered over West Texas in the 1950s? Is it the call of the crazy Comanche wind? Could it be the 360º vista of flat horizon that makes you feel smack dab in the center of the universe? Or is it just so damn boring out in the literal middle of nowhere that even the most mundane moments seem miraculous? Some say the lack of stimulation in the environment creates the perfect zendo. Some say there is nothing else to do but make music and dance. The answer may be an unspoken magic in the soil, water, or the incessant wind. Perhaps it is the eccentric and innovative culture of the people who have settled and thrived in Lubbock. A place of howling dust storms and magic rainbows, paradox and prairie dogs, the religious right and Zen mystics, flying saucers and shooting stars, supernatural outlaws and perfect masters of self, Lubbock, Texas, is certainly a place that engenders strong emotions, as evidenced by the interviews in this book.

Austin, Texas, 2005

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.